I have been to a lot of track meets lately. I personally am more at ease when intellectually detached from my own physicality, but I have two sons who seem completely at one with their muscles and sinews. They embrace the challenge of cultivating strength and agility. They put in the work, and as a result, they sprint and they jump—they defy gravity. They stand tall.

Each time they race past me on a track I watch with a thrill, and I crane to see the end result. I am unfailingly proud, and so astonished, that anything of me at all might be contained in these two packages of health and effort and intent. If only young me could have seen them, I think. Maybe I would have tried to be an athlete too! It is an unexpected joy to gain self-belief through the existence of your children.

Track meets involve bursts of breakneck speed, feats of impressive strength, and demonstrations of incredible endurance. There’s also a lot of waiting around, if you’re hoping to see something specific. Recently I stood under an end-zone scoreboard for an hour or so as novice high jumpers tried to make height on the infield. A lanky, easy-going senior stopped to chat and we watched a freshman distance-runner lope past, easily outpacing her peers in the 3200M. I remarked on her potential and her steady, relentless pace; he nodded thoughtfully.

“I watched her run the mile earlier this season,” he said. “She had tears streaming down her face as she went by, she was in so much pain, but her pace never changed.” He said this neutrally, neither condemning or approving—simply acknowledging that she was the Real Thing. He jogged off without further comment.

In track and field, every event can become a specialty with its own strategy, its own equipment, or even its own identifiable body type. Teammates balance their focus on individual, specialized skills with a shared, whole-body approach to fitness. For some, practices offer a low-stress way to build in a daily work out and hang with friends. For others, the team functions as a support group in their quest for personal excellence. The mindfulness of the latter group transcends athleticism: it is an outlook, a way of life. It’s a little intimidating.

A dear friend of mine from high school coaches biathletes (they’re the ones who combine target shooting with Nordic skiing). He claims that anyone can benefit from taking up biathlon, because it’s all about connecting motion to breathing, and breathing to heartbeat. Like track and field standouts, exceptional biathletes are those who consciously integrate the management of their physical, emotional, and intellectual health.

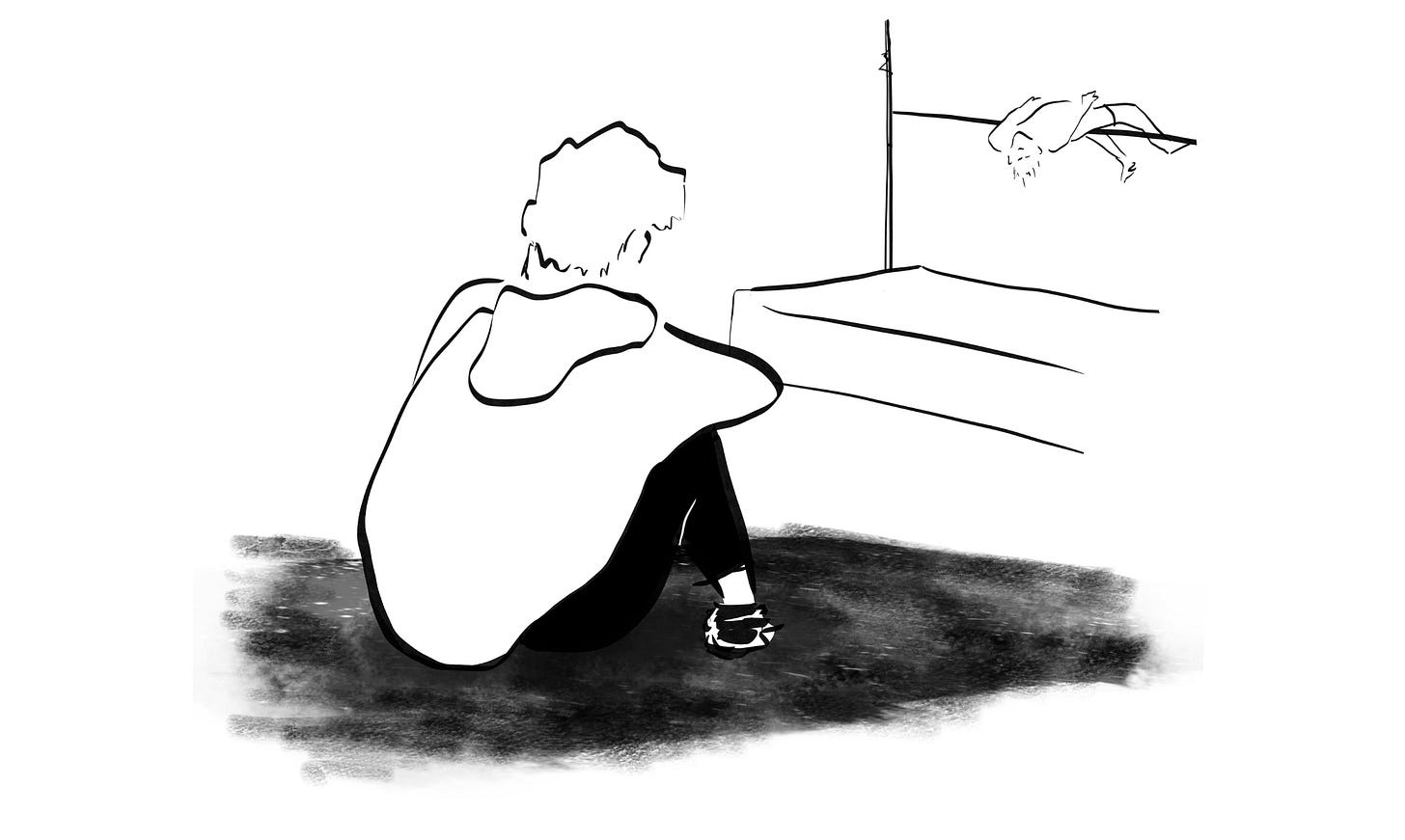

My older son was on hiatus from his particular specialty for a while this spring, due to an inflamed Achilles’ tendon. I told my friend how impressed I had been with my kid’s self-discipline in holding back from something he loves so much.

“Recovery is part of the sport,” my friend reasoned. “I can’t tell you how many biathletes get that wrong, thinking they have to train week after week relentlessly. Same with a lot of marathoners.” His tone reminded me of the distance runner who had dispassionately assessed his freshman teammate. This was simply a Truth.

Later in the evening my friend’s partner asked me about my doodling (she qualifies as a superfan, having enthusiastically purchased several prints two Christmasses ago). I sheepishly admitted to a “doodling block”—not anything insurmountable, but something that had seemed to grow as my work commitments eased. I was redefining work/life balance and hadn’t yet discovered where doodles fell in the whole mix. Was it possible, I wondered aloud, that I could only be creative when otherwise overtaxed and in need of escape?

My friend interjected almost offhandedly, “But you’re in recovery, right?”

I could feel something shifting in my thinking as I stared at him—I was conscious of an almost physical sensation of epiphany. He gestured to the coffee table book I’d showed them earlier. “You worked on this for what, three years? Five years? Seems like this pause is about right. Your body will tell you when you’re ready to get back into it.”

It seemed obvious to my friend that I have been taking a hiatus in order to stay in peak condition. I’ve been sitting with that idea for several weeks now, and it still startles me. How could it be that, after a lifetime of being the obvious non-athlete in every room, a sports analogy had unlocked my thinking?

So I’m working on acceptance, and reframing these rest periods as self-discipline. I’m an athlete! I’m an aging, soft-at-the-edges athlete, honing her skills for an internal sport so specialized that most people will never witness me at a finish line.

And that’s great. Like that freshman with tears running down her cheeks, or my jumping-bean sons, I’m really only competing against myself.

Here are some bits and bobs I’ve come across during this recovery period that you might also enjoy:

Did you know that Britain has a reality show about portrait painting?? It’s called “Portrait Artist of the Year,” and there are several seasons available on YouTube. In each finale, the winner paints a museum-commissioned portrait (I love this finale featuring Alan Cumming).

If you want to have your mind blown by superhuman athletic feats, watch these highlights from a world-class high jumping competition. It took place in 2014, but the winner is the current Olympic and World Champion.

One of our sons keeps showing us horrible—horribly funny?—videos of this person “testing” heavy equipment. If you are constantly perplexed by the humor of the younger generation (get off my lawn!!) your mileage may vary.